The exhibition ‘Happy in Berlin?’ follows in the footsteps of a small party of literati Brits in Berlin. It’s fittingly presented at the Literaturhaus (Literature House) in Berlin. Christopher Isherwood and Vita Sackville-West lead the way.

When you enter the grand building, the tune of ‘Exactly like You’, sung by Louis Armstrong in 1930, transports you back to the period while you climb the stairs to the first floor where the exhibition rooms lie. The staircase, with its dark vintage wallpaper, already makes you feel as if you were in one of the tenements Christopher describes in ‘Goodbye to Berlin’ as “monumental safes”. The first image that greets you shows a vending machine providing information for tourists. A choice of 180 buttons offered the visitor different addresses of shops, police stations, consulates, theatres etc – all free of charge. Who knew that these existed in 1925?

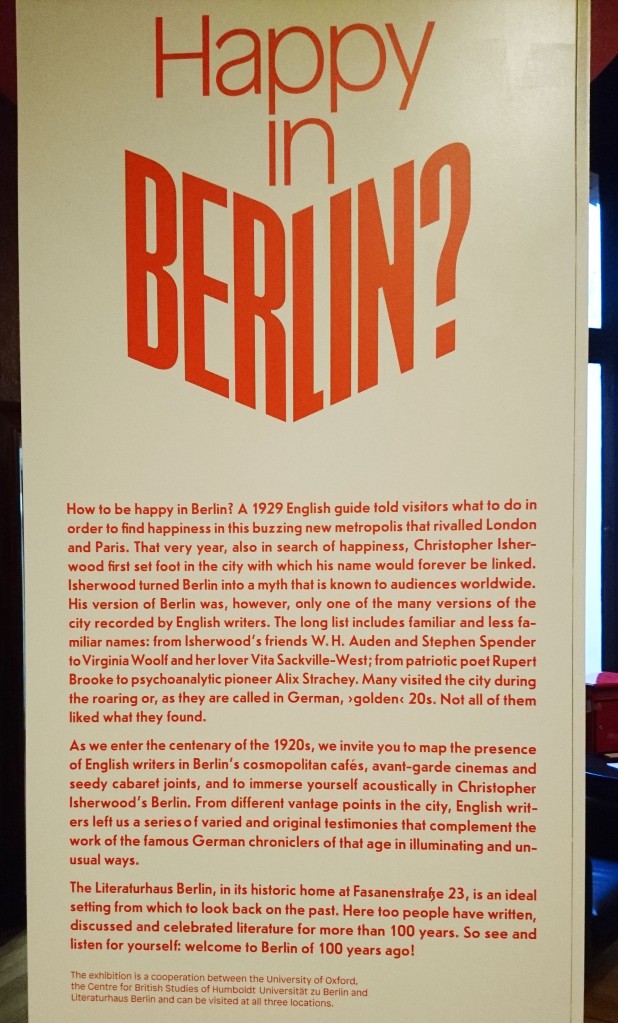

Various quotes accompany you en route to the first floor, among them “Paris is the place to loaf in; London is the place to work in; Berlin is the place to do great things in with great, grand gestures” from John Chancellor’s 1929 travel guide ‘How to be Happy in Berlin’, which also lends the exhibition its title. Chancellor was the penname of the British crime writer Ernest Charles de Balzac Rideaux Willett (1900–71). A quote by Eddy Sackville-West, taken from a letter to E.M. Forster in 1928, reveals: “[Berlin is] triumphantly, aboundingly ugly – so ugly that the mind is left quite free to pursue its own fantasies, unhindered by Beautiful Buildings. […] I was dragged about at night from one homosexual bar to another. The behaviour is perfectly open. There are even large dance spaces for inverts. And some of the people one sees, huge men with breast like women & faces like Ottoline, dressed as female Spanish dancers.”

The exhibition at the Literaturhaus is mainly made up of two rooms. The first introduces you to the addresses which were key to the visitors presented. Among these places was the radio tower, constructed in 1926 and a symbol of Berlin’s progressiveness. Vita Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf dined in its restaurant, high above the city, when Virginia came for a visit. There are also the cabaret The Eldorado, the hottest joint in the city where queer folk enjoyed Berlin’s decadent night life, and the Cozy Corner, a shabby working-class gay bar and one of Christopher’s favourite haunts. The coffee house culture, represented by the famous Café des Westens and the Romanische Café, contributes another aspect to the life of Berlin’s bohème. At their tables, news and jobs were brokered. Psychoanalyst and Bloomsbury Group member Alix Strachey spent many happy hours at the Romanische Café reading, writing and soaking up its vibrant atmosphere. A lesser-known attraction of Berlin’s cultural life was Russian cinema. Soviet films were censored in Britain but could be seen in German cinemas.

The second room immerses the visitor into Christopher’s world. A postcard from him to Stephen Spender is displayed and you can listen over headphones to the message on the card, read by Justin Reddig. Various objects in the room are linked to passages from ‘Goodbye to Berlin’. A camera with photos of his lovers prompt the lines: “I am a camera with its shutters open…” A projector shows extracts from films, which Christopher would have seen, e.g. ‘Pandora’s Box’ (1929) and ‘Comradeship’ (1931). The latter is set in a miners’ milieu and pictures the men with their well-built bodies taking a thorough shower after work; certainly a very pleasing scene to Christopher and his friends. A small radio by the exit stands for an interview with Christopher and it’s touching to hear his voice.

While Christopher felt very much at home in Berlin, Vita and Virginia were more reserved towards the rough city. Virginia’s sister Vanessa Bell captures Vita’s feeling in a letter to her son Julian Bell in 1929: “Vita is in a state of rage and despair. She hates the Germans, who don’t let her take her dog for a walk freely, drive in her car without passing 3 medical exams or do any of the things she likes […] The Germans are ugly, incredibly badly dressed, kind. The food tasteless. I begin to long for France.”

Although, it is always nice to be in Christopher’s company and to catch a glimpse of Vita’s aristocratic life, it would have been nice to learn a bit more about Eddy Sackville-West’s or Alix Strachey’s adventures in Berlin. Also, painfully absent from what is otherwise a gem of an exhibition, curated by Stefano Evangelista and Gesa Stedman, is the lesbian scene with its clubs, such as the Violetta Club or the Topkeller, which Vita might have explored during her stay. The exhibition would have equally benefitted from a slightly wider angle, including the American writer Margaret Goldsmith, Vita Sackville-West’s lover in Berlin, who later moved to London. She wrote the 1928 novel ‘Patience geht vorüber’, a lesbian romance with a love triangle. She is only briefly mentioned in a different part of this exhibition, located miles away at the Humboldt University. That section covers the areas Politics, Psychoanalysis and Pleasure, which are described as three ‘major draws to British writers to Berlin in the early 20th century’. It revolves around lesser-known figures such as Evelyn, Countess Blücher, Alix Strachey, Elizabeth Wiskemann and Diana Mosley, and delves deeper into the circle of Brits in Berlin.

‘Happy in Berlin?’ is a joint project between the Literaturhaus, the Centre for British Studies at the Humboldt University and Oxford University, where the Bodleian Library focused, until 11 July, on the political clashes between Communists and Fascists as seen by Stephen Spender.

The exhibition is accompanied by a series of talks, which can still be followed online on its Youtube channel.

In addition there is the website ‘Berlin through English Eyes’, an ongoing project set up by the makers of the exhibition.

Also, if you want to find out what exactly John Chancellor recommended to his fellow countrymen, a PDF version of his book is available online.

Last but not least, something to take home and keep after the displays have been taken down on 31 July 2021, is the catalogue to accompany the exhibition: ‘Happy in Berlin? English Writers in the City. The 1920s and Beyond’.

By Sabine Schereck